Inside the Anglo-Saxon Shield-Wall: Exploring the Battle of Maldon

An analysis of an Old English heroic poem

The year is AD 991 and a Viking army rages across east England. Led by the fearsome King Olaf, the warrior crews of ninety-three longships pillage the undefended lands of the Anglo-Saxons and plunder the town of Ipswich. Riding to meet them is Earl Byrhtnoth, commander of the Anglo-Saxon army of King Æthelred. It has been over a century since Alfred the Great’s decisive victory over the “Great Heathen Army” at the Battle of Edington and half a century since Alfred’s grandson Athelstan crushed the Vikings at Brunanburh and unified the English people. Æthelred, known to history as the Unready,1 is a far cry from his predecessors, and under his reign, England is once again vulnerable to the raids of the fearsome Northmen.

The two armies meet along the banks of the River Blackwater, near the small town of Maldon, Essex. There, they clash in a battle that ends disastrously for the Anglo-Saxons. Byrhtnoth is killed along with most of his warriors. And the triumphant Vikings must be paid off with a hefty tribute of 10,000 pounds. In the years that follow, the Vikings will return again and again, fended off only by sizable bribes. At last, in 1016, King Svein Forkbeard will depose Æthelred and reign as King of England, Denmark, and Norway.

The Battle of Maldon represents a pivotal moment in the history of the Anglo-Saxons and their struggles against the Vikings. But what makes it especially interesting is that it is the subject of one of the greatest works of Old English poetry: The Battle of Maldon.

Like nearly all poetry of the Anglo-Saxon period, The Battle of Maldon is anonymous, written sometime in the late 10th or 11th century. Only a fragment of the work survives—a mere 325 lines—missing both beginning and ending. Even with these gaps, the poem offers us rare insight into the battle, and, by extension, to Anglo-Saxon warfare in general. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the official historical record, Maldon and the year 991 are summed up briefly:

A.D. 991. This year was Ipswich plundered; and very soon afterwards was Alderman Britnoth slain at Maldon. In this same year it was resolved that tribute should be given, for the first time, to the Danes, for the great terror they occasioned by the sea-coast. That was first 10,000 pounds. The first who advised this measure was Archbishop Siric.2

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is replete with such accounts. Battles often merit little more than a few lines: naming the leaders, giving the location, and summing up the aftermath. But what we seldom see is anything like a “closeup” of battle, a description of specific troop movement, tactics, the emotions of those involved, the deeds of the men who fought and died. It can be frustrating for those of us turning to these historical texts for a glimpse into early medieval warfare and a sense of what it was like to fight in an Anglo-Saxon shield-wall.

In The Battle of Maldon, however, we do have access to these sensory details. The poem gives us everything, from tactics to epic speeches, to the brutal blow-by-blow exploits of individual soldiers. This, along with its rich literary qualities, makes the text invaluable as a primary source for warfare in early medieval Britain.

The poem fragment begins with Byrhtnoth, the commander of Æthelred’s forces, preparing his troops for battle:

Then Byrhtnoth ordered every warrior to dismount,

drive off his horse and go forward into battle

with faith in his skills and with bravery.3

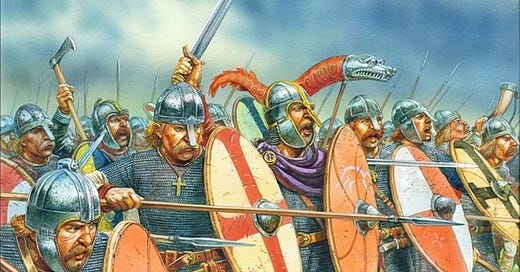

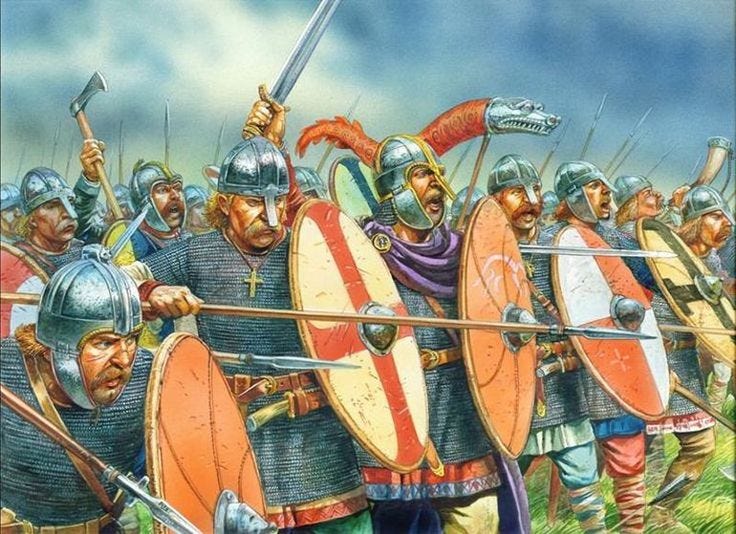

The Anglo-Saxons, like their Viking enemies, fought predominately on foot. Horses were used generally as a means of transportation. Warriors would ride to a battle site, but for the actual fighting, they would dismount and stand together in tight lines of infantry with interlocking shields. This formation, used by Saxon and Viking alike, is known as the shield-wall. The horses used by the people of this era were smaller and lighter than the mounts of later medieval knights and would be ineffective at charging such a wall of shields and spears.

Earl Byrthnoth assembles his men in this standard formation. But even before battle is joined, the poem presents us with some grim foreshadowing of what is to come. One warrior, named only “Offa’s young son,” sees that Byrhtnoth “was no man to suffer cowardice.” What follows is rich in symbolism:

He sent his best falcon flying from his wrist

to the safety of the forest and strode into the fight;

thereby one could well see that the youth

would not be weak in the turmoil of battle.

Why does the warrior send away his falcon? This moment hints at the inevitable doom of the Saxon army. The falcon flies away to “the safety of the forest,” while Offa’s son enters the fight. He is ridding himself of all distraction, narrowing his focus for battle. By sending his falcon away, he protects the bird from the violent death that awaits him.

Meanwhile, another warrior, Eadric, is eager for battle:

At once he hurried forward

with his spear. He feared no foe

for as long as he could lift his shield

and wield a sword: he kept his word

that he would pierce and parry before his prince.

In this passage, we encounter another key aspect of Germanic warrior culture: the function of oaths. In the tight-knit communities of early medieval Europe, oaths bound a warrior to his lord, and a lord to his warriors. Before battle, it was customary for these warriors to boast (often under the influence of ale and mead) of what they would do on the battlefield, the courage they would demonstrate, the enemies they would slaughter. Battle, with all its terror and brutality, is the ultimate testing ground for these oaths, proving who is truly a valiant warrior, and who is merely an empty boaster. Eadric here has sworn his vows, and he will keep them, fighting as long as he maintains the physical capacity to hold a shield and sword.

But not all in the English army are so eager for battle. In the very next lines, we hear how Byrhtnoth moves among his men, instructing and exhorting them:

Then Byrhtnoth began to marshal his men.

He rode about and advised, he told his men

how they should stand firm, not yielding an inch,

he bade them grasp their shields in their hands

tightly and upright, and not be afraid.

On the surface, this passage looks simply like a general inspiring his troops before a battle. But if we look more closely, something troubling emerges. What Byrthnoth is actually doing here is teaching his men the basics of soldiering.

“This is how you stand,” he is saying. “This is how you hold a shield. Hold on tight. Don’t be afraid.”

We might expect this kind of training to occur at camp or in the safety of an English stronghold. But when it is taking place in front of the enemy army, shortly before battle, it is deeply concerning. Why don’t these men already know how to fight? And if they’re just now learning how to keep their shields up, how do they stand a chance against the army of Vikings beyond the river? These Norsemen are the tenth century’s most fearsome combatants, men the poet describes as “slaughter-wolves.”

Imagine a boxing match. In one corner, we have the champion. His professional record is 20-0, with fifteen wins coming by way of knockout. He is standing there, doing a little shuffle with his feet, moving his arms to stay warm, breathing in and out regularly. His coach is standing nearby, hyping him up, going over their game plan, which they’ve been rehearsing throughout the months-long training camp.

In the other corner, we have the challenger. His record is 0-0. This is his boxing debut. His limbs are also moving, more from fear than as part of a warmup. His coach, meanwhile, is using this opportunity to give him a crash course in Boxing 101.

“Stand like this,” he says. “Left foot in front, balance your weight. Now throw your jab. No, not like that, like this! Keep your hands up, elbows tight. Don’t drop your right hand when you jab. Don’t lean forward. Don’t raise your chin. Stop telegraphing your punches!”

Even if we have zero context aside from this brief observation, it is obvious who will win. Martial training takes time, whether it’s for boxing or fighting in a tenth-century shield-wall. You really need to have covered the basics before you show up to a battle.

But Byrhtnoth is in a tough spot. He’s leading a standard Anglo-Saxon army, made up partly of seasoned warriors like Eadric and Offa’s son. Mostly, though, his army consists of the fyrd, a levy of peasants, called up in times of war. These guys are not professional soldiers. They don’t spend their days training with spears and shields. They’re farmers and craftsmen. For many, judging by these lines in the poem, this is their very first time handling war gear.

Now the Anglo-Saxons make contact with their Viking enemies. A messenger from the Viking army speaks with Byrhtnoth. The Norsemen’s offer is simple: give us money and we won’t destroy you:

“It is better for you

to buy off our raid with tribute than that we,

so cruel, should cut you down in battle.”

But Byrhtnoth has his orders. He’s to put a stop to the Viking raiders, not by tribute, but by force. His response is brave, heroic, like something straight out of the movie 300:

He grasped his shield

and brandished his slender ashen spear,

resentful and resolute he shouted his reply:

“Can you hear, you pirate, what these people say?

They will pay you a tribute of whistling spears,

of deadly darts and proven swords,

weapons to pay you, pierce, slit

and slay you in the storm of battle.

Listen, messenger! Take back this reply:

break the bitter news to your people

that a noble earl and his troop stand over here—

guardians of the people and of the country, the home

of Ethelred, my prince — who will defend this land

to the last ditch. We’ll sever the heathens’ heads

from their shoulders.”

It goes on for a few more lines, but you get the gist. Byrhtnoth is standing his ground, even though he’s leading an army of farmers against a pack of Viking wolves. “You want payment?” he’s saying. “How about a payment of spears and arrows and swords?”

With these bold words, Byrhtnoth assembles his men along the bank of the River Blackwater. The Norse army of King Olaf is lined up on the far bank and they need to cross to continue their raid. For a while:

the troop on either side could not get at the other

for there the flood flowed after the turn of the tide;

the water streams ran together.

Neither side can attack as of yet. But eventually, the tide ebbs, allowing the Vikings to cross.

But the Saxons have the advantage of terrain. They are the ones in the defensive position. Like Obi-Wan-Kenobi in Revenge of the Sith, Byrhtnoth can confidently say, “I have the high ground!” And, like a savvy commander, he exploits this advantage:

[Byrthnoth] ordered

a warrior to defend the ford; he was Wulfstan—

Ceola’s son - the bravest of brave kin;

with his spear he pierced the first seafarer

who stepped, unflinching, on to the ford.

Two proven warriors stood with Wulfstan,

Ælfere and Maccus, both brave men.

These heroes, picked, we can safely assume, from among the ranks of the seasoned warriors and not the farmers who have just received basic military instruction, hold the ford successfully against the Viking invaders. The poet tells us:

Nothing could have forced them to take flight

at the ford. They would have defended it

for as long as they could wield their weapons

So far, everything is going well for Byrhtnoth. He’s been given the unenviable task of driving off an army of fearsome Viking invaders. And he’s managed very well. He is forcing his enemies to come across a few at a time and be slaughtered by the elite warriors defending the ford. This kind of scenario is like the Holy Grail for military commanders, a proven way for smaller, inferior forces to defeat larger and more powerful armies.

Think of the great upsets of ancient and medieval history and how defensible terrain played a significant role in those victories. In the Hundred Years’ War, the English used the advantage of elevation and difficult terrain combined with their superior archery to defeat much larger, heavily armoured forces at the battles of Crecy, Poitiers, and Agincourt.4

Or the famous Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC, in which the Spartans, along with their Greek allies, managed to inflict terrible losses on the much larger Persian force by defending a narrow pass along the sea. It is not until the Persian King Xerxes finds a way to bypass this bottleneck and surround them (with the help of a Greek traitor) that the Spartans lose their advantage and are slaughtered.

Byrhtnoth should be fine then as long as his enemies do not find another way to ford the Blackwater. But what does he do? The Vikings ask if they can cross the river, and Byrhtnoth, against all reason, agrees to this request:

Then, in foolhardy pride, the earl allowed

those hateful people access to the ford.

What? Why would he agree to this?

If we, as modern readers ask that question, imagine how much more keenly the Anglo-Saxon audience would have felt this frustration. It is this foolish decision that leads to the great tragedy of English loss and the humiliation of having to pay enormous tribute to the Vikings. A lot of modern scholarship focuses on this passage and how the poem characterizes the earl’s decision. The poet is pretty sparse regarding Byrhtnoth’s motivations. In the original Old English, he refers to the earl’s ofermod, translated here as “foolhardy pride” (other translations have “overweening pride” or “overconfidence”). For whatever reason, Byrhtnoth thinks he can win this fight “fairly,” without exploiting the natural terrain. He seems impatient to get the battle started. Once he pulls back his defenders from the ford, he says:

“Now the way is clear for you. Come over to us quickly,

warriors to the slaughter. God alone can say

who will control the field of battle.”

Note the urgent tone, the impatience. Byrhtnoth is tired of the waiting, tired of the deployment, tired of the maneuvering. He wants to throw down and see who wins. And if he has to concede the tactical advantage to bring about a swift resolution to the conflict, so be it!

The Vikings cross the river, and immediately, the poet foreshadows the ominous conclusion:

Then the battle,

with its chance of glory, was about to begin.

The time had come for all the doomed men

to fall in the fight.

Attending the field are creatures that always presage carnage in Germanic battle poetry. The poet draws attention to how “the ravens wheeled and the eagle circled overhead, craving for carrion.” Their presence here confirms what we and all the warriors present already know: a great slaughter is about to take place.

At last, the battle begins in earnest. The poet tries to capture the madness and chaos of what such a battle must have been like. He describes several things all at once, with no clear point-of-view, creating a sense of mayhem:

They sent their spears, hard as files,

and darts, ground sharp, flying from their hands.

Bow strings were busy, shield parried point,

bitter was the battle. Brave men fell

on both sides, youths choking in the dust.

Here we have ranged warfare (spears and arrows) occurring simultaneously with hand-to-hand combat (shields parrying points). Already, people are dying on both sides. At this point, there’s no attempt to differentiate the deeds or the deaths of specific people or even specific sides. Everyone is hurling spears and shooting arrows, thrusting with swords and blocking with shields. And everywhere, young men are dying.

After this disorienting introduction, the poet begins zooming in, describing the actions of specific, named English warriors. Despite the horrors and the bloodshed, the Anglo-Saxons are characterized by bravery, by a bloodthirsty zeal to earn their glory and make good on the boasts of the night before. While “the dead sank to the earth,” the poet writes, “the brave men stood firm in battle, each sought eagerly to be first in with his spear.”

None is more eager than Byrhtnoth himself, on whose perspective the poem now fixes. Foolish though he may have been to allow the Vikings to cross the river uncontested, there is no denying his valour. He steps forward, setting his sights on one of the Northmen. The Viking warrior is quicker, wounding Byrhtnoth with his thrown spear. But though injured, the Saxon lord retaliates:

Then he flung his spear in fury at the proud Viking

who dared inflict such pain. His aim was skillful.

The spear split open the warrior’s neck.

Byrhtnoth follows this up with another kill:

he swiftly hurled a second spear

which burst the Viking’s breastplate, wounding him cruelly

in the chest; the deadly point pierced his heart.

Two enemies down in quick succession. Things are looking good for Byrhtnoth. He’s got the makings of a fearsome killstreak. And he rides this high, gripped by a curious mix of bloodlust and religious devotion:

The brave earl, Byrhtnoth, was delighted at this;

he laughed out loud and gave thanks to the Lord

that such good fortune had been granted to him.

This moment marks the zenith of Byrhtnoth’s success. But while he offers up prayers to God and laughs at the destruction of his heathen enemies, his fortune swiftly changes. A Viking casts a javelin, piercing his side. Byrhtnoth’s companion, Wulfmær, kills the enemy who wounded his lord, but another seafarer charges Byrhtnoth, for “he had it in mind to snatch away his treasures—his armour and rings and ornamented sword.”

Byrhtnoth doesn’t let a little thing like a spear wound to the side stop him. He draws his fancy, ornamented sword and engages the oncoming enemy, slashing at this mailed chest. But this battle is not like what we see in Hollywood versions of medieval combat. This is not a one-on-one fight. While Byrhtnoth fights one enemy, another blindsides him, attacking from the side:

he destroyed the earl Byrhtnoth’s arm.

The golden-hilted sword dropped from his hand.

He could hold it no longer, nor wield

a weapon of any kind.

Weaponless and wounded, Byrhtnoth’s fighting ability is now severely diminished. But our doomed hero is courageous to the last, calling out encouragement and exhortation to his men:

Then still the old warrior

spoke these words, encouraged the warriors,

called on his brave companions to do battle again.

And as the Vikings bear down upon him, breaking through the lines of the Anglo-Saxon shield-wall, Byrhtnoth prays again, thanking God “for all the joys I have known in this world” and asking that “my soul may depart into Your power in peace.”

His final prayers uttered, Byrhtnoth meets his end:

He heathens hewed him down

and the two men who stood supporting him;

Ælfnoth and Wulfmær fell to the dust,

both gave their lives in defence of their lord

This marks the turning point of the battle. With Byrhtnoth slain, panic and despair ripple across the English ranks. Those whom the poet calls “certain cowards” begin to retreat, leaping atop horses and in the hopes of escaping the battle before the total slaughter begins. The text lists many by name—Odda, Godric, Godwine and Godwig—forever memorializing their cowardice, forever shaming them and their descendants. Their flight is not merely an act of cowardice in the eyes of the poet and his Anglo-Saxon audience. It is also “unlawful,” a severing of the oaths of loyalty which bind a lord to his followers. With phrases like “forsaking Byrhtnoth,” “forgetting how often his lord had given him the gift of a horse,” and “forgetting their duty,” the poet marks these men as betraying their proper duty, violating the warrior’s code of conduct. You do not abandon your lord, even when he is dead. Battle is where a warrior proves himself and earns the rewards he has been given by his lord. To run from battle after accepting gifts of horses, armour, and arm-rings, is to betray all that a warrior should be.

The poet adds:

and more men followed than was at all right

had they remembered the former rewards

that the prince had given them, generous gifts.

Keep in mind that the men who are running are not the untrained farmers but the professional warriors whose whole function is to protect their lord and land in exchange for money and gifts.

The poet reflects on what the warrior Offa once said about this issue:

that many who spoke proudly of their prowess

would prove unworthy of their words under battle-stress.

This issue—that men boast wildly in the safety of the mead hall but often prove unworthy of those boasts when faced with actual battle—becomes the principal theme of the poem. As Mike Tyson famously quipped, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.” Contact with the enemy—the proverbial “punch in the face”—proves whose boasts are empty and whose are backed by action.

And while many of Byrhtnoth’s warriors prove unworthy and ungrateful, many more stay to fulfill their vows through battle.

the brave men hastened eagerly:

they all wished, then, for one of two things—

to avenge their lord or to leave this world.

One young warrior, Ælfwine, makes the theme of loyalty and living out one’s oaths explicit. He exhorts his fellow warriors to fight, reminding them:

“Think of all the times we boasted

at the mead-bench, heroes in the hall

predicting our own bravery in battle.

Now we shall see who meant what he said.”

Ælfwine, for one, backs up his brave words with braver deeds. After finishing his speech, he attacks and “pierce[s] a pirate’s body with his spear.” Others follow after Ælfwine’s example. The warriors Offa and Leofsunu reiterate their commitment to fight until they can fight no more, and thus avenge their earl’s death. Even Dunnere, whom the poet describes as a “lowly churl,” a peasant, shames the wealthy warriors who have fled:

he cried out loud

and asked every man to avenge Byrhtnoth’s death

One by one, the Saxon warriors call out bravely, perform great deeds, and fall in battle against the overwhelming force of the Viking army. There is no possibility of winning this fight. Nor even is there a chance at a moral victory, a “lose the battle to win the war” like we see at the Alamo or Thermopylae. No, this is an unmitigated disaster. Byrhtnoth’s proud and foolish choice to let the Vikings cross the Blackwater has led not only to his own death but to that of every warrior who stands and fights with him. The only end to this battle is humiliation for the English, hefty tribute for the Vikings.

And yet, the poet is determined to record the deeds of the men who fall, who gave their lives despite the grim impossibility of their position. They are heroic in the face of sure defeat, courageous for the sake of loyalty, of being true to their word. They embody the Germanic warrior ethos: manly resignation in the face of unbending fate.

We have lost the true ending to this poem which relates the rest of the battle and its aftermath. Instead, the story breaks off in the midst of the carnage. And as the fragment draws to a close, it is Byrhtwold (not to be confused with Byrhtnoth) who has the final word. He is an “old companion” a grizzled veteran of the shield-wall:

“Mind must be the firmer, heart the more fierce,

courage the greater, as our strength diminishes.

Here lies our leader, hewn down,

an heroic man in the dust.

He who now longs to escape will lament for ever.

I am old. I will not go from here,

but I mean to be by the side of my lord,

lie in the dust with the man I loved so dearly.”

Byrhtwold’s words encapsulate the poem’s elegiac theme. Life is fleeting. Death is the fate of every man. What do we become if we run from adversity and renege on our oaths in the face of adversity? He who runs will “lament for ever.” In the face of sure defeat, as a horde of Vikings smashes through the crumbling shield-wall, killing the Saxons to a man, the doomed warrior Byrhtwold makes his stand. His stoic resolve nearly leaps from the page, speaking to the heroic ethos of his warrior culture.

So concludes the surviving lines of The Battle of Maldon. As a historical document, it gives us invaluable insight into the material aspects of early medieval warfare such as tactics and weaponry as well the immaterial such as troop morale and the warrior code. And as a work of literature, the poem is raw and powerful, capturing the brutality and chaos of the shield-wall and the nobility and courage of the warriors who fight in it. With its celebration of courage, lament for the fallen, and exploration of both the tragic foolishness of Byrhtnoth and his admirable heroism, The Battle of Maldon offers a complex, multi-layered perspective on warfare. Alongside the original Anglo-Saxon audience, we are left to sit in the ambiguity, joining in the poet’s profound meditation on honour and shame, courage and cowardice, life and death.

Actually, his nickname was originally Æthelred Unræd, meaning the “ill-advised”

I’m using the Kevin Crossley-Holland translation from The Anglo-Saxon World Anthology (Oxford University Press, 2009).

See my previous Substack post about the Battle of Crecy: What was a medieval battle really like? A detailed look at the famous Battle of Crecy