In my last post, I talked about why I think fantasy (or historical fiction) authors should read primary sources to understand the period from which they are taking inspiration. In this post, I’d like to model that reading by looking at how a specific source, Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, gives us insight into how medieval battles were fought. Like many fantasy authors, I write stories that feature large, detailed battle scenes. To make these as authentic and realistic as possible, I have found it extremely useful to read actual medieval accounts of warfare.

In this post, I’ll be focusing on the Battle of Crecy (1346), a major battle during the Hundred Years’ War that saw an overwhelming English victory over the French. The Middle Ages encompass a thousand years of history and an entire continent, so we cannot take a single battle as characteristic of all medieval warfare. However, even reading only one account will help us recognize many of the conventions and realities of medieval battle.

About the source.

While he was not a soldier himself, Froissart interviewed men who had participated in the conflicts he records in his Chronicles. At other times, he borrowed heavily (with attribution) from first-hand accounts written by veterans of a particular battle.1 In his prologue, he explains his process for gathering accurate information:

[I] have been led by a constant inclination to seek the company of various nobles and great lords … Thus, I have always made inquiries to the best of my ability about the exact course of the wars and other events which have occurred.

So while Froissart had no direct combat experience, he did run in the circles of those who did. Note that he mentions specifically “nobles and great lords.” This focus on the concerns and deeds of the nobility, and lack of interest in the goings on of the common person (who made up the majority of any medieval army) betrays a typical attitude shared by the vast majority of historians in the Middle Ages that those who ranked among the lower classes were generally unworthy of being recorded in history, except for when they interact with the nobility (such as in the famous Peasants’ Revolt of 1381).

Deployment

Like nearly all medieval battles, the fight at Crecy served as the culmination of a long military campaign. The English, led by King Edward III, had been rampaging through Normandy, taking towns, defeating small garrisons, and looting the countryside. In response, King Philip VI of France raised his army and went out to meet them.

Firstly, Froissart tells us how the English king “divide[d] the army into three bodies.” These bodies, commonly called “battles” or “wards” were standard for the organization of medieval armies. They consisted of the van (or vanguard), the middle, and the rear. When deployed for battle, the van would be on the right flank, the rear on the left flank, and the middle in the centre.

Each of these battles contained a mix of cavalry, infantry, and archers. Froissart writes that “in the Prince’s division [the vanguard] there would have been about eight hundred men-at-arms, two thousand archers and a thousand light infantry including the Welsh.”

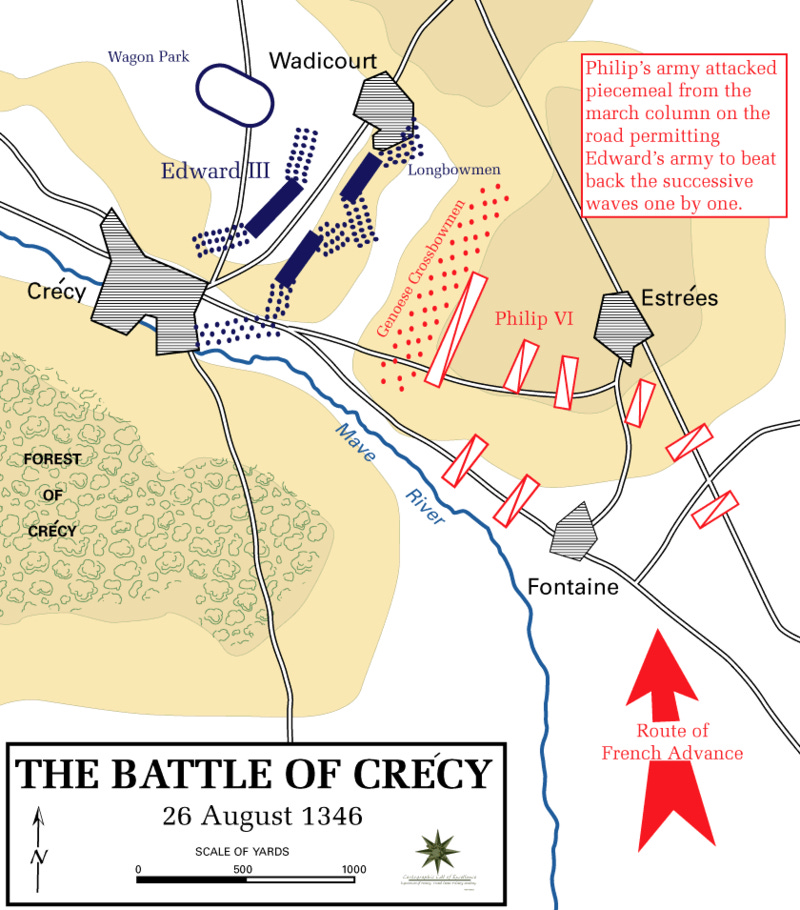

Although greatly outnumbered, the English had the advantage of terrain. Edward III arrayed his army on a hillside, flanked on each side by a small village (Wadicourt and Crecy). By the time the French arrived at the battle site, the English had already chosen their ground, allowing them to dictate the terms of the fight.

Froissart offers a detailed description of how the English positioned themselves:

The English, who were drawn up in their three divisions and sitting quietly on the ground, got up with perfect discipline when they saw the French approaching and formed their ranks, with the archers in harrow-formation and the men-at-arms behind. The Prince of Wales’s division was in front. The second, commanded by the Earls of Northampton and Arundel, was on the wing, ready to support the Prince if the need arose.

In contrast to the English and their well-ordered divisions, the French approached the battle in disarray. One of Philip’s knights, Le Moine, gives him the sound advice to wait until the rear of his army has time to catch up and then allow them to rest before engaging the enemy. Other lords reject this cautionary advice, however, and urge the king to attack the English that evening, without allowing their men to rest or taking the time to form orderly divisions. Froissart says that “each wanted to outshine his companions, regardless of the advice of the gallant Le Moine … There were too many great lords among them, all determined to show their power.”

Due to the urging of these glory-seeking knights, the French army “rode on in this way, in no order or formation, until they came within sight of the enemy.” But things get worse from here:

The French lords – kings, dukes, counts and barons – did not reach the spot together, but arrived one after another, in no kind of order. When King Philip came near the place where the English were and saw them, his blood boiled, for he hated them. Nothing could now stop him from giving battle. He said to his Marshals: ‘Send forward our Genoese and begin the battle, in the name of God and St Denis.’

The Genoese were mercenaries, heavily armoured and carrying crossbows, serving as the French answer to the English (and Welsh) longbows. Medieval battles often opened with ranged warfare, as archers and crossbowmen attempted to weaken the opposing side before the hand-to-hand combat began.

There is a significant problem with Philip’s plan, however, and that is that the Genoese are exhausted:

[King Philip] had with him about fifteen thousand Genoese bowmen who would sooner have gone to the devil than fight at that moment, for they had just marched over eighteen miles, in armour and carrying their crossbows. They told their commanders that they were not in a state to fight much of a battle just then.

The French have no tolerance for these excuses. They order the Genoese forward while a thunderstorm begins raging (Froissart certainly knows how to set a dramatic scene). The Genoese advance and begin shooting at the English line. The English archers respond and rain destruction on their enemies:

At this the English archers took one pace forward and poured out their arrows on the Genoese so thickly and evenly that they fell like snow. When they felt those arrows piercing their arms, their heads, their faces, the Genoese, who had never met such archers before, were thrown into confusion. Many cut their bowstrings and some threw down their crossbows. They began to fall back.

King Philip is, once again, unimpressed by his Genoese crossbowmen. He orders the French cavalry (consisting of knights and men-at-arms) to advance on the English and slaughter their own mercenaries along the way.

The King of France, seeing how miserably they had performed, called out in great anger: ‘Quick now, kill all that rabble. They are only getting in our way!’ Thereupon the mounted men began to strike out at them on all sides and many staggered and fell, never to rise again.

The English archers take advantage of the confusion and unleash their arrows on the heavily armoured horsemen, who fare little better than the Genoese:

The English continued to shoot into the thickest part of the crowd, wasting none of their arrows. They impaled or wounded horses and riders, who fell to the ground in great distress, unable to get up again without the help of several men.

The French now commit their full force to the attack, and hand-to-hand fighting rages along the front of the English line. At one point, the earls fighting in the ward of Prince Edward (also known as the Black Prince), send word to King Edward asking for aid. The king refuses, telling them to “let the boy win his spurs,” meaning, that this is the prince’s moment to earn glory and honour for himself on the battlefield, without being bailed out by his father.

Ultimately, Prince Edward holds off the French attack and the English win a decisive victory. In explaining the reasons for the French loss, and the unusually high casualties, Froissart writes:

The lateness of the hour harmed the French cause as much as anything, for in the dark many of the men-at-arms lost their leaders and wandered about the field in disorder only to fall in with the English, who quickly overwhelmed and killed them. They took no prisoners and asked no ransoms, acting as they had decided among themselves in the morning when they were aware of the huge numbers of the enemy.

…

Among the English there were pillagers and irregulars, Welsh and Cornishmen armed with long knives, who went out after the French (their own men-at-arms and archers making way for them) and, when they found any in difficulty, whether they were counts, barons, knights or squires, they killed them without mercy. Because of this, many were slaughtered that evening, regardless of their rank. It was a great misfortune and the King of England was afterwards very angry that none had been taken for ransom, for the number of dead lords was very great.

This brutality has come to characterize the Battle of Crecy as well as much of the Hundred Years’ War. Medieval warfare was supposed to be governed by a code of chivalrous conduct, which included detailed provisions for the capture and ransom of well-born enemies. When we look at accounts of actual battles, however, such as this passage from Froissart’s Chronicles, we see that real soldiers, caught up in the heat of battle or motivated by greed, often disregarded the rules and regulations of warfare.

I hope you enjoyed this walk through one of the most famous battles in medieval history. Warfare in the Middle Ages is a vast and diverse topic, and I hope to write more of these posts in the future, exploring the details of other medieval battles. Please leave me a comment or send me an email if you found this interesting or if you have any questions.

Froissart’s description of the Battle of Crecy is one of these, indebted heavily to the account written by the French knight Jean Le Bel.