"Woe to the conquered": How the Gauls sacked Rome and the geese saved it.

The dramatic conclusion to Livy's epic historical account

Back in February, I published a post looking at the Battle of the Allia in 390 BC. At the Allia, the Gauls and Romans met in what was to be the first of many conflicts between their peoples, culminating in Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul in 50 BC. In this first battle, however, it is the Gallic force — the tribe of Senones under their chieftain Brennus — that emerges victorious, overcoming the discipline and order of Rome through both ferocity and ingenuity. In the last post, we looked at how the Roman historian Titus Livius (aka. Livy) recounts with horror how poorly the Fabii tribunes managed their army at the Allia, and how easily the Romans are routed and unmanned by the terrifying barbarians.

The Gauls also are stunned by the easy victory they have gained over a people famed for their military prowess. Fresh from this unexpected success, they advance on the city of Rome.

The Romans, meanwhile, are thrown into a state of panic and grief. Believing their army has been nearly entirely destroyed, the people mourn what they believe to be a total catastrophe:

As for the Romans, inasmuch as more, on escaping from the battle, had fled to Veii than to Rome, and no one supposed that any were left alive except those all alike, both the living and the dead, and well nigh filled the City with lamentation.1

Believing they are the last of Rome’s defenders, the few who remain in Rome begin making preparations to face the advancing horde. But with such a small force, they are limited in how much of the city they can defend. Sadly, the Romans realize they cannot protect the whole of Rome, so they withdraw to the Capitoline, one of the city’s seven hills:

For having no hopes that they could protect the City with so small a force as remained to them, they resolved that the men of military age and the able-bodied senators should retire into the Citadel and the Capitol, with their wives and children; and having laid in arms and provisions, should from that stronghold defend the gods, the men, and the name of Rome.

The Capitoline holds the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus (chief deity of the whole Roman pantheon), the most significant temple in Rome, and a symbol of Roman power, both civic and religious. This hill, then, serves as the perfect place to stage the last defense of Rome.

But there is limited room on the Capitoline. Many among the city’s plebeian population are forced to flee the city. This host, “too large for so small a hill to receive, or to support with so meagre a supply of corn, streamed out of the City as though forming at last one continuous line, and took their way towards Janiculum.” And while the young and able-bodied Romans prepare to defend the Citadel, the elderly must remain in the undefended city, where they prepare to meet their deaths at the hands of the barbarians with stoic resolve.

Livy focuses specifically on the patricians who had once served as curule magistrates (dictators, consuls, censors, etc.).. These venerable old men return to their homes, lining the Roman Forum. There they dress themselves in their finest robes and sit patiently in their ivory chairs, awaiting the ravaging horde.

The Gauls, meanwhile, enter Rome in a state of superstitious awe. The night that followed their victory at the Allia has seen “their lust for combat cooled.” Sober and wary, they roam the streets and pour into the Forum, finding no one to oppose them:

They found the dwellings of the plebeians fastened up, but the halls of the nobles open; and they hesitated almost more to enter the open houses than the shut, —so nearly akin to religious awe was their feeling as they beheld seated in the vestibules, beings who, besides that their ornaments and apparel were more splendid than belonged to man, seemed also, in their majesty of countenance and in the gravity of their expression, most like to gods.

These old magistrates, dressed in the full splendour of their office, make the Gauls cautious. Livy suggests that the superstitious barbarians even believe them to be the gods of the Roman people.

But the illusion does not last forever:

While they stood reverentially before them, as if they had been images, it is related that a Gaul stroked the beard of one of them, Marcus Papirius, — which he wore long, as they all did then, — whereat the Roman struck him over the head with his ivory mace, and, provoking his anger, was the first to be slain; after that the rest were massacred where they sat; and when the nobles had been murdered, there was no mercy then shown to anyone; the houses were ransacked, and after being emptied were given to the flames.

And so the Gauls begin the sack of Rome. Seeing Marcus Papirius bleed and die seems to break the spell cast by these still old magistrates. Looting and burning fill the city, everywhere that the Romans have abandoned in their defense of the Capitoline Hill.

These defenders of the Citadel must remain where they are, watching their city burn, listening to the sounds of grief and slaughter. And yet, they remain firm in their resolve, meeting their fate with the same stoic determination that saw the elderly magistrates calmly await their deaths. Livy writes:

Yet, oppressed as they were, or rather overwhelmed, by so many misfortunes, nothing could alter their resolve; though they should see everything laid low in flames and ruins, they would stoutly defend the hill they held, however small and naked, which was all that Liberty had left. And now that the same events were occurring every day, like men grown used to grief, they had ceased to feel their own misfortunes, looking solely to their shields and the swords in their right hands as their only remaining hope.

At last, the time to use those shields and swords arrives. The Gauls, having pillaged their way through the city, set their sights on the Citadel:

At daybreak the signal was made; and the entire host, having formed up in the Forum, gave a cheer, and raising their shields above their heads and locking them, began the ascent.

The Gauls are confident of victory. And why shouldn’t they be? They already faced and routed the Roman army at the Allia. And they have had full rein to plunder the city at their leisure. What danger could this small force of defenders pose?

But, as Livy has taken such great pains to point out, the Roman army at the Allia was a poor representation of Roman might. Terribly mismanaged, the soldiers were led by tribunes who forsook discipline, piety, and tactics. The men of the Citadel will make no such mistake:

The defenders on the other hand did nothing rashly or in confusion. At all the approaches they had strengthened the guard-posts, and where they saw the enemy advancing they stationed their best soldiers, and suffered them to come up, persuaded that the higher they mounted up the steep the easier it would be to drive them down. They made their stand about the middle of the declivity, and there, launching their attack from the higher ground, which seemed of itself to hurl them against the foe, dislodged the Gauls, with such havoc and destruction that they never attempted to attack in that manner again, with either a part or the whole of their strength.

This forceful defense of the Capitoline takes the Gauls by surprise and forces them to abandon the idea of taking the hill by direct assault. Instead, they resolve to lay siege to the Citadel and starve out the defenders. The only issue is that they had not prepared for this possibility. In their wild passion, they’ve burned up most of the grain supplies in Rome. To provision their horde, they must send out a large part of their army to pillage the surrounding countryside.

Rome is in dire straits, its defenders beleaguered, surrounded on all sides. Yet all is not lost. In suitably dramatic fashion, Livy returns to the hero of this story, Marcus Furius Camillus. Camillus, thanks to the political machinations of his enemies, has been living out his days in exile in the nearby town of Ardea. Even banished, Camillus is a true, heroic Roman. For, as Livy writes, “Camillus was languishing there in exile, more grieved by the nation’s calamity than by his own.”

Happily for the Roman people, it is to Ardea that the roaming bands of Celts happen to come. To Livy, this is the work of Fortune itself, a sign that the gods will save Rome from peril. He says, “Fortune’s own hand guided them [the Gauls] to Ardea, that they might make trial of Roman manhood.”

The people of Ardea are alarmed by the news of the approaching barbarians. They hold council to determine the best course of action. And here Camillus steps in. He addresses the people of Ardea, telling them that he will lead them against the Gauls, promising them victory. He begins by reminding them of his fearsome resume: “‘Twas by this art [of war] that I stood secure in my native City: unbeaten in war, I was driven out in time of peace by the thankless citizens.” Now that war has come again, to Rome as well as Ardea, a man of Camillus’s unrivalled talent is once more in demand. He will lead them to a sure victory over the Senones.

For the barbarians are not nearly as dangerous as they seem. With characteristic Roman prejudice, Camillus admits that the Celtic warriors are big, strong, and ferocious, but that they lack the discipline to be truly formidable:

That people now drawing near in loose array has been endowed by nature with bodily size and courage, great indeed but vacillating; which is the reason that to every conflict they bring more terror than strength.

In this speech that Livy assigns to his hero Camillus, he relies on a Platonic understanding of the human psyche, in which the soul is divided into three components: reason, spirit, and appetite. For a person’s soul to be harmonious, reason must be in control, subsuming the passions and appetites under its command. In Phaedrus, Plato explains this idea using the metaphor of a chariot. Harnessed to the chariot are two winged horses: one black (representing the appetites) and one white (representing spirit). Holding the reins is reason, the charioteer. As long as reason directs spirit and appetite, both will function as they are meant to, drawing the chariot up toward the heavens. But if one or both of the horses should pull away and determine the chariot’s direction, then reason ceases to function as it should, becoming captive to the whims of the powerful beasts that are spirit and appetite.

This model applies not only to individuals but to whole cultures as well, a point readily made by Classical philosophers. Civilizations like that of the Greeks or Romans are governed by reason, which leads them to be a people of laws and to operate on the battlefield with rigorous discipline. The Celts, meanwhile, are ruled by a spirit of reckless courage and ravenous appetites. As Camillus observes:

They greedily gorge themselves with food and wine, and when night approaches they erect no rampart, and without pickets or sentries, throw themselves down anywhere beside a stream, in the manner of wild beasts.

The Gauls’ lack of discipline and reason makes them no better than beasts, who similarly are ruled by appetite. And though wild beasts are undeniably strong and intimidating, they are no match for the cold discipline of the Roman army.

For these reasons, Camillus promises the Ardeans an overwhelming victory. “Follow me in force,” he tells them “not to a battle but a massacre.” The men of Ardea take up Camillus’s call, putting their trust in him as commander. And everything goes just as he predicts:

They had not left the city very far behind them, when they came to the camp of the Gauls, unguarded, just as he had prophesied, and open on every side, and, giving a loud cheer, rushed upon it. There was no resistance anywhere: the whole place was a shambles, where unarmed men, relaxed in sleep, were slaughtered. Those, however, who were farthest off were frightened from the places where they lay, and ignorant of the nature of the attack or its source, fled panic-stricken, and some ran unawares straight into the enemy

This moments begins the turning of the tide. It is a sign that the gods have not abandoned the Roman people. And while Camillus leads the Ardean soldiers to slaughter the Gauls, the Roman army at Veii has been recouping and gathering strength. They are ready to march again and to take back Rome from the invaders. There is just one problem:

The time was now ripe to return to their native City and wrest it from the hands of the enemy; but their strong body lacked a head.

Camillus is the only candidate to lead this army, but he is still an exile, and cannot leave Ardea without violating Roman law. Committed to “preserving the proper distinctions,” the soldiers ask permission of the Senate, whose members are still trapped in Rome. They send a young man floating down the Tiber on “a strip of cork,” who manages to slip past the besiegers and into the Citadel. When the Senate hears the army’s wishes, they recall Camillus from exile and appoint him dictator of Rome.

But while Camillus assumes his role as dictator and takes command of the forces at Veii, the Gauls attempt once more to take the Capitoline, this time by stealth. They find a “cliff near the shrine of Carmentis [that] afforded an easy ascent,” and begin scaling this cliff under cover of night. At last, they “reached- the summit, in such silence that not only the sentries but even the dogs —creatures easily troubled by noises in the night —were not aroused.”

Things look bleak for the Romans. The sentries have failed them. Even the dogs are not awakened by the intruders. Are they all about to be slaughtered while they sleep by these stealthy barbarians?

Enter, the geese, the unlikely heroes of Livy’s tale. For as the Gauls creep up the Capitoline:

they could not elude the vigilance of the geese.

Because these geese were sacred to the goddess Juno, the Romans kept them alive, despite being starved out and under siege. This pious act is now handsomely rewarded:

This was the salvation of them all; for the geese with their gabbling and clapping of their wings woke Marcus Manlius, —consul of three years before and a distinguished soldier, —who, catching up his weapons and at the same time calling the rest to arms, strode past his bewildered comrades to a Gaul who had already got a foothold on the crest and dislodged him with a blow from the boss of his shield. As he slipped and fell, he overturned those who were next to him, and the others in alarm let go their weapons and grasping the rocks to which they had been clinging, were slain by Manlius. And by now the rest had come together and were assailing the invaders with javelins and stones, and presently the whole company lost their footing and were flung down headlong to destruction.

Through the intervention of the geese and Marcus Manlius’s quick, decisive action, the Capitol is saved once more. But the siege continues, and the Romans are suffering from starvation:

Day after day they looked out to see if any relief from the dictator was at hand; but at last even hope, as well as food, beginning to fail them, and their bodies growing almost too weak to sustain their armour when they went out on picket duty, they declared that they must either surrender or ransom themselves, on whatever conditions they could make.

The Gauls, meanwhile, are more than happy to bring the siege to an end. For they too are starving, as well as suffering from rampant disease. For these reasons, Livy writes, “the Gauls were hinting very plainly that no great price would be required to induce them to raise the siege.”

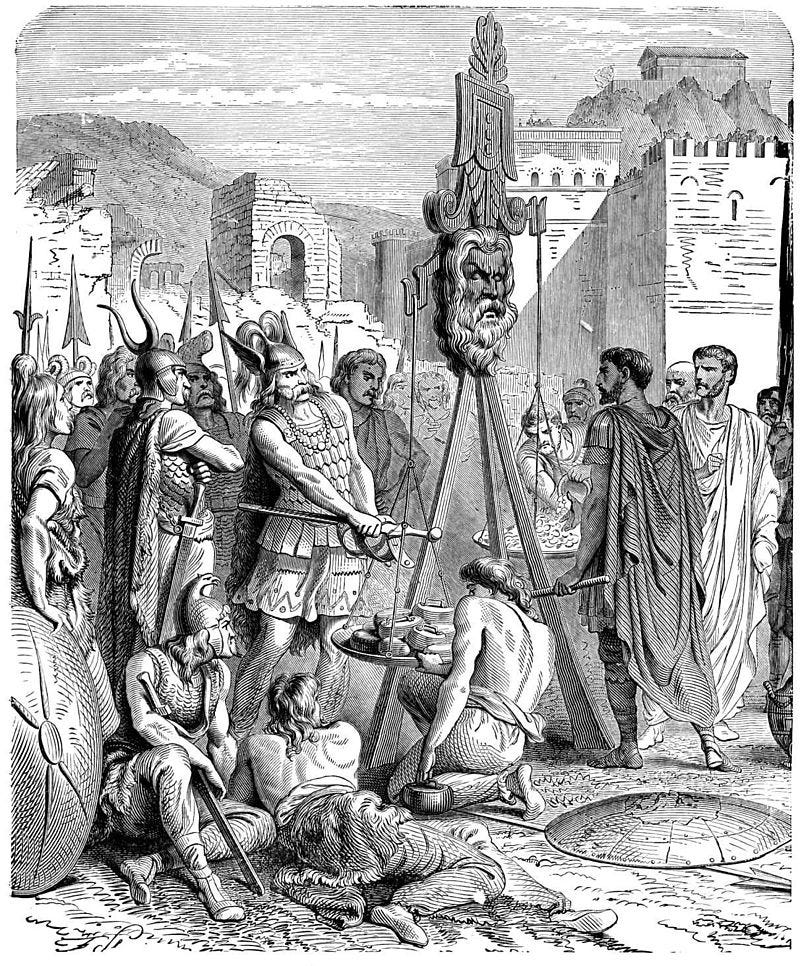

A conference is held between the leaders of both parties, the tribune Quintus Sulpicius and Brennus, chieftain of the Senones. They agree upon a payment of “a thousand pounds of gold,” which Livy derides as “a foul disgrace,” for the Romans are a people “destined presently to rule the nations.” The Gauls add further insult to this “disgrace” by using what Livy insists are dishonest scales to weigh the Roman tribute. When Sulpicius complains, Brennus utters one of the most iconic lines in all of Roman history:

The insolent Gaul added his sword to the weight, and a saying intolerable to Roman ears was heard, —Woe to the conquered!

“Woe to the conquered,” or, in Latin, “vae victus,” typifies the might-makes-right philosophy that Livy consistently attributes to the Celts. In their first parlay with the Romans at Clusium, the Senones told the Romans that “they carried their right at the point of the sword and that all things belonged to the brave.” Now, Brennus drives home that point. By placing his sword onto the scales, he insists that all the things the Romans claim to hold most dear — law, order, justice — can be upheld only by the strength of their army. And these same ideals can be just as easily overthrown by the sword. Livy calls Brennus the “insolent Gaul” and castigates the barbarians for their dishonest, brutish subversion of justice. But the Romans themselves operate under the same moral principle. The Gauls are merely more blunt about it.

In the following passage, Livy immediately tries to wipe away the disgrace the Romans have suffered:

But neither gods nor men would suffer the Romans to live ransomed. For, by some chance, before the infamous payment had been consummated, and when the gold had not yet, owing to the dispute, been all weighed out, the dictator appeared and commanded the gold to be cleared away and the Gauls to leave. They objected vehemently, and insisted on the compact; but Camillus denied the validity of that compact which, subsequently to his own appointment as dictator, an inferior magistrate had made without his authorization, and warned them to prepare for battle

Camillus couches his position in terms of legality: a lesser magistrate, Sulpicius, oversaw the paying of tribute. Because Sulpicius acted without the authorization of the dictator, the agreement is not legally binding. But while Camillus invokes Roman law, he is more than ready to enforce his interpretation of justice at the point of the sword. While making his case legally, Camillus simultaneously warns the Gauls “to prepare for battle.”

In the battle that follows, the dictator once again exploits the barbarian lack of reason. While he positions his men strategically, “in preparation which the art of war suggested,” the Gauls charge recklessly “with more rage than judgment.” This time, Livy assures his Roman readers, “now fortune had turned; now the might of Heaven and human wisdom were engaged in the cause of Rome.” And as he gleefully describes how Camillus smites the Gallic host, Livy seems to endorse Brennus’s assertion that it is the sword that determines right from wrong. For it is by crushing the Gauls in battle that the Romans prove their moral right and demonstrate that they possess the favour of the gods. Camillus’s vengeance is the vengeance of Heaven itself. And the Gauls pay dearly for looting the sacred city:

Here the carnage was universal; their camp was taken; and not a man survived to tell of the disaster.

By defeating its enemies, Rome has redeemed itself as a nation and has proven the rightness of its civilization, its laws, and its governance. Likewise, it is by violence that Camillus has proven his own justness. His victory in battle absolves him of the crimes that saw him exiled. Whatever the truth of the accusations made against him, all is swept away by the totality of his victory:

The dictator, having recovered his country from her enemies, returned in triumph to the city; and between the rough jests uttered by the soldiers, was hailed in no unmeaning terms of praise as a Romulus and Father of his Country and a second Founder of the City.

And so Livy concludes his account of the Battle of the Allia and the sack of Rome in 390 BC. While not as well-known as the later sack in AD 410, this is a moment that defines both the Roman people and their centuries-long dealings with the Celts. For the remainder of the Republic’s history, the Gauls remain an ever present foe, outlasting other infamous enemies of Rome such as Carthage or the Macedonian Empire. For three centuries, Rome will make war against the Gauls, pitting Roman discipline and tactics against Celtic strength and ferocity. The Romans will not achieve lasting victory until Caesar’s conquest of Gaul in 50 BC. But by that point, the Republic is also in decline, receiving its death blow in 27 BC with the rise of Caesar’s heir Octavian as Augustus Caesar, the first Emperor of Rome. Throughout its tumultuous history, the Republic is haunted by Brennus’s ominous warning. In the hands of a virtuous man like Camillus, the sword protects the Republic, maintaining the justness of its laws. But in the hands of a tyrant like Augustus, that same sword becomes the undoing of law and order and tradition, of everything it was meant to uphold.

Living through the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius, Livy looks back with longing on the early days of Rome’s history. He contrasts the decadence and tyranny of the Roman Empire to a golden age when men like Camillus used their strength to protect rather than oppress, and when Rome was strong and virtuous enough to recover from setbacks like the Allia and triumph over its enemies.

Related Posts:

“All things belong to the brave”: Gauls, Romans, and the Battle of the Allia

Inside the Anglo-Saxon Shield-Wall: Exploring the Battle of Maldon

Throughout this post, I am citing the Loeb Classical Library version translated by B. O. Foster.

Livy probably didn’t know either - he was writing several centuries later. While he had access to records (eg lists of consuls and magistrates), there were clearly gaps, and he ends up describing the same events more than once. Shortly after this, Camillus fights two campaigns against the same neighbours of Rome in what may be a muddling of one occurrence.

Ah, interesting read. It's just so hard to tell which moments in Livy's account are true, even ignoring the bias. Enjoyed the, thank you.